Fairhaven Sermon 11-26-2023

Rev. Parson discusses the Royal Canadian Mint's new coins featuring King Charles without a crown, symbolizing the evolution of leadership and identity in contemporary society.

This weeks sermon by Rev. Dylan Parson focuses on a significant shift in the portrayal of British royalty, specifically the transition from Queen Elizabeth II to King Charles. Rev. Parson notes the Royal Canadian Mint's new dollar coins featuring King Charles, emphasizing the notable absence of a crown in his portrait. This contrasts starkly with the consistent depiction of Queen Elizabeth with a crown throughout her reign.

Rev. Parson reflects on this change as more than a mere alteration in imagery. He observes that King Charles' portrait lacks any traditional indicators of royalty, such as royal robes or regalia. The sermon likely uses this observation as a metaphor or starting point for deeper discussions, possibly exploring themes of leadership, identity, and the evolving nature of symbols in society. The choice to focus on the absence of the crown and other royal symbols in King Charles' portrait might serve as an allegory or prompt for a broader spiritual or philosophical exploration in the sermon.

Transcript

I saw this past week that over a year after the death of Queen Elizabeth II, the Royal Canadian Mint has begun to release its first dollar coins bearing the image of the new king, King Charles. So after over 70 years now of Canadian coins bearing the image of Queen Elizabeth, with a crown on her head, always, alongside dozens of other countries around the world, not just the UK but all the former Commonwealth countries, a new face will be seen on coins and bills. And the image that's come out of the Mint of how they're going to do it, it's notable I think that King Charles' portrait will not include a crown. This is a really major departure from the way that his mother was portrayed.

Queen Elizabeth from her youngest years, whenever she was first coronet, coroneted? Have always had a crown, but nothing in King Charles' portrait really gives you indication that he's even a king, if you didn't know. He's not wearing royal robes, not that you know the furs, anything like that. Instead he's just shown in a suit and a tie. He could be any well-dressed businessman, lawyer, if you don't know who you're looking at, it's just a guy in a nice suit.

But surrounding the edge of the portrait is a caption that has been on every British coin for a very long time, and it's in Latin, a phrase that makes his office very clear. And it says, Charles III, D.G. Rex, which is short for the Latin, Dei Gratia Rex, which means King by the grace of God.

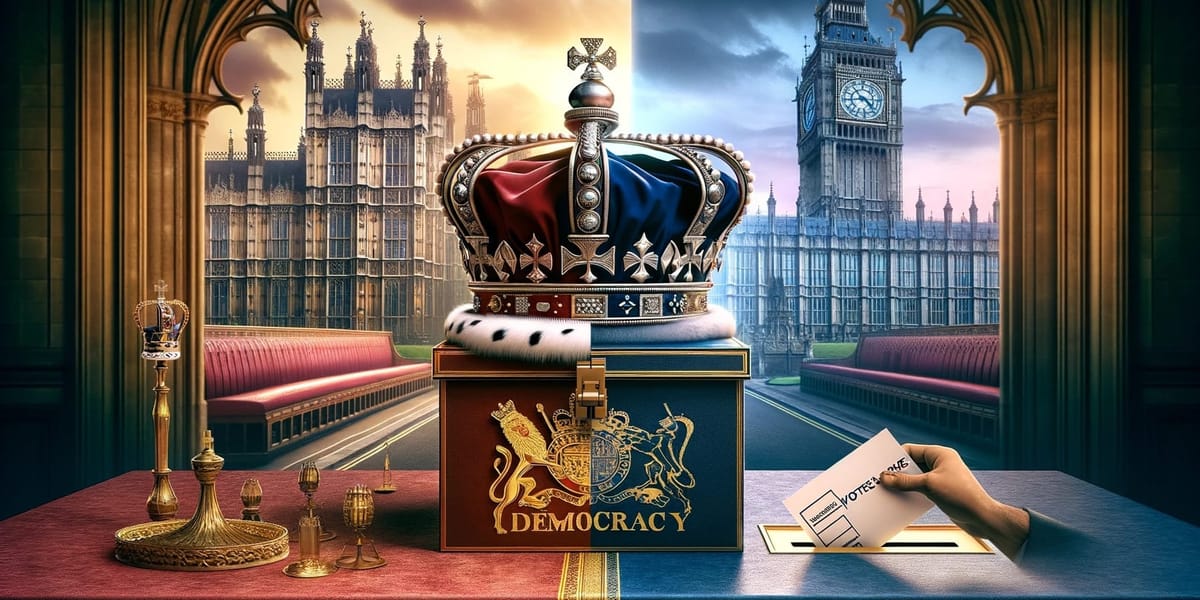

And I tell you what, nothing makes me feel more like a patriotic American than monarchy. King by the grace of God is just super gross to me. It's quite the claim, one that I would never dare make about any American president, no matter how much I liked him. Don't tell Peg, but I know that many, many, many Americans love the pageantry and the drama surrounding Buckingham Palace, but I can't help it, to me it's goofy.

This guy is king because he happened to be born first among his siblings, because of the unique configuration of who his ancestors strategically married among other nobility, all kinds of maneuvering that went on by rich people in long-dead European empires. That to me is not the same thing as King by the grace of God. There's a lot of other stuff that went into that whole thing. I think it's a bizarre way to get your face on dozens of nations' coins, gain control over tens of billions of dollars' worth of land, and the religious elements of the thing.

Some people like this the best, but it mortifies me the most. The king or queen of the UK, as you may or may not know, serves as defender of the faith in their capacity. They're supreme governor of the Church of England, which is why there are all sorts of prayers and anointings and so on during the coronation. The king is involved with the appointment of bishops in the Church of England, all that sort of thing.

I just don't like it. No matter how much it's been reformed, no matter how much it's just ceremonial now, I'm too American. I'm too deeply steeped in the idea of democracy. I think that's genuinely a good thing.

And honestly, my commitment to democracy is not just in the political realm. The United Methodist Church, democratically governed, the whole thing, top to bottom. Our bishops are elected. And at the bottom, you know, the nominations committee, church council, church conference, our whole system means that if you're a member of the United Methodist Church, you have a say over the whole thing.

So while Great Britain is used to an unelected king, the Roman Catholic Church is used to a pope and bishops whom they have no control over, this American Methodist is used to neither of those things. And so today, Christ the King Sunday, where we focus on Jesus as king, kind of rough for me. I and I suspect you because you're as American as I am, deep down, just don't get what a king is, what a king is for. We're supposed to elect the people in charge of us.

We're supposed to have a say in how we're ruled. We might make bad decisions, but that's all right. But that is not the case in the kingdom of God. God sits enthroned over all things.

This is an image you see over and over in the Psalms, especially God sits enthroned over creation. God is the first and the last, the final authority, the great judge, the one with the power to create and destroy. The difference, unlike for every human monarch in history, is that God is unfailingly good. Hear those words from our Psalm this morning, Psalm 100.

Know that the Lord is God. It is he that made us and we are his. We are his people and the sheep of his pasture. Enter his gates with thanksgiving and his courts with praise.

Give thanks to him, bless his name, for the Lord is good. His steadfast love endures forever and his faithfulness to all generations. So to some great extent, understanding or really getting a king like King Charles or Louis XVI or Kaiser Wilhelm or something doesn't really help us understand what it means that Christ is our king at all. We're dealing with a different kind of king here, a different kind of kingdom.

And so it makes sense that on this day that we celebrate Jesus being king, our scripture readings, and this is kind of surprising, but it makes sense. They spend very little time talking about his throne, his glory, his royal court, all of those things come up, but there are plenty of passages in scripture where we could really dig into this kind of grandeur of God's rule. Instead, as we celebrate Christ the king, we hear from the prophet Ezekiel in our first reading about how he's a shepherd gathering his lost sheep together into a flock, feeding them, taking care of them, sorting them. And from Matthew's gospel, our second reading, we hear about how Jesus, the king, is poor.

Stranger, imprisoned, sick. And these are not the classic examples that come to mind when we think about human royalty. King Charles III of his coronation sat in a grand throne wearing a crown that consisted of five pounds of gold and jewels. That crown's barely ever broken out because you can't realistically wear that much gold on your head without hurting your neck for very long.

That's just one piece of a royal collection that's gathered in large part from colonies conquered all around the world. It's impossible to miss the point of what those jewels are supposed to demonstrate. The British empire itself, all that power, all that grandeur is conveyed by these jewels. That's why they go all out.

King Jesus though, Jesus says you're pretty much guaranteed not to see him. You're pretty much guaranteed not to notice him in front of your face. And so this entire passage here in Matthew 25 functions both as a grace and as a warning, a spiritual checkup to see if you are prepared when you meet your king, prepared to even recognize him. We're given a vision here in Matthew 25.

This isn't a parable so much as a vision. We're given a vision of the final judgment where the human one, the son of man, is sitting on his throne. He's surrounded by the angelic court. He's surrounded by all the angels.

We see this heavenly throne room here. And he, the king, is doing something that a shepherd would do, not necessarily a king. He's separating the sheep, his flock, from the goats who are these disobedient creatures. They'll be sent to eternal punishment, what some translators call the chastening or the pruning is a good rendition of the Greek there.

And Jesus gives us the criteria for how this judgment's going to go down. To those he calls the sheep, the king says in Jesus's vision, Inherit the kingdom that was prepared for you before the world began. Why? Why did they get that? Well, the king says, I was hungry and you gave me food to eat. I was thirsty and you gave me a drink.

I was a stranger and you welcomed me. I was naked and you gave me clothes to wear. I was sick and you took care of me. I was in prison and you visited me.

And the sheep here don't just say, Woo, yeah, great. They're confused. Despite ending up on the right side of things, they're completely confused. They don't understand what they did to get all this.

When did we do that? When did we see you? You know, we think we'd have noticed if the king of the universe was standing right in front of us, especially if we fed you or offered you a drink or gave you clothes to wear or visited you while you were sick or in prison. We don't remember any of that. Ah, the king replies, It's not quite so simple. I assure you that when you have done it for the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you have done it for me.

And the goats, of course, ask the same question when the king points out they did nothing for him. When did we even see you? We don't remember that. We don't remember this challenge. And again, the king says, I assure you that when you haven't done it for the least of these, you haven't done it for me.

How easy would it be to be generous and helpful and gracious if we knew that Jesus himself, the king, was standing in front of us in need of help? That's not so hard, right? It's another thing entirely to love other people whom Jesus calls his brothers and his sisters. Put it in terms of modern royalty, right? If for whatever reason Prince Charles wandered into church today, King Charles wandered into church today, or some American equivalent of royalty, I don't know, that's like Taylor Swift, Joe Biden, Elon Musk, it'd be easy for us to roll out the red carpet, doing our absolute best to impress them, to welcome them into our space. Another story maybe if it's just some random person from Moorbrook, especially if they're visibly different, income, race, disability, age. Are we able to muster up that same hospitality and grace to somebody who doesn't look like a king at all? Jesus is revealing a great mystery for us here, and one he wants to make sure that we recognize because it's a life or death issue for him.

You know, whenever we take communion, somehow that bread and that juice are transformed into the body and blood of Christ. We don't understand it, but somehow it's transformed. Here I think Jesus is saying exactly the same thing. I think he's saying that that exact same thing occurs constantly as we live and move through the world.

The least of these, my brothers and sisters of Jesus whom we encounter, especially if they're in need, are in some way, literally Jesus Christ himself. Oh, but all those homeless people downtown, that guy who's high and yelling on the sidewalk, teenage kid in prison for pulling a gun to rob another kid, they don't look like Jesus. I certainly hope Jesus doesn't look like those people, our king. So we ask, when did we see you, Lord? I don't like this either.

I don't know how to get out of it. This is one of those passages I don't know how to rework to get out of it. And this is one of those ones that makes you want to try. The more I think about this vision from Jesus in Matthew 25, the more it frightens me because how many times have I seen him and done nothing? How many more times will I do so in my lifetime? But we cannot say that we don't know what the king looks like when he's telling us flat out.

We cannot say we don't know. One preacher writes about this vision where the sheep and the goats are judged that salvation is something we discover when we least expect it. And clearly that's absolutely correct, which should be obvious for those of us who worship an almighty God who let himself get crucified without putting up a fight. Salvation where we least expect it.

And yet also Jesus is telling us exactly where to expect it. Even as we'll never cease to be surprised by it, even as we might be resistant to the form salvation takes. By his own example, by stories like this, we see in Jesus what real kingship looks like. Humble, kind, obedient, even unto death on a cross in Paul's words.

More like a shepherd or even a sheep than any king we've ever seen in this world. And additionally, we see what the true eternal kingdom of God looks like. The first or last, different part of Matthew. Jesus for the suffering is finally served.

And the least of these, the lowliest of people are in some supernatural way, the presence of the Lord himself. And all of this reveals the inevitable passing away of all earthly kings, all earthly rulers, all earthly nations, including our own, that don't come close to measuring up to God's eternal reign. And even as he's a different kind of king, he's still a king. In the end, whenever we get to this vision of the final judgment, the Lord is the only one who's fully sovereign.

He's the one who's sitting on that throne, the only one with final power. We don't get a vote. Whether you're a sheep or a goat, you don't get a vote. God is God in the end, no one else.

In the end, it is the one who is lamb and shepherd and king who sits on the holy throne, who divides the sheep from the goats, even as we struggle or even resist seeing him in the faces we see the moment we walk out of the store. Here are these words from the English priest and poet Malcolm Guy. He wrote this poem for Christ the King. Our king is calling from the hungry furrows while we are cruising through the aisles of plenty.

Our hoarding screens us from the man of sorrows. Our soundtracks drown his murmur, I am thirsty. He stands in line to sign in as a stranger and seek a welcome from the world that he made. We see him only as a threat, a danger.

He asks for clothes. We strip search him instead. And if he should fall sick, then we take care that he does not infect our private health. We lock him in the prisons of our fear, lest he unlock the prison of our wealth.

But still on Sunday, we shall stand and sing the praises of our hidden Lord and King. May you see the Lord even as you go forth in this place, even as his face is hidden. Tells us where he's going to be. Name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.

Amen.